Bobbe

Bobbe

I first met

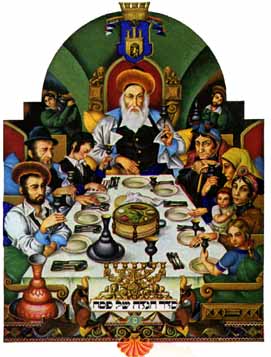

him at Passover, when I was five. He was an annual guest at my Zayde's

(grandfather's) seder, the ritual meal that celebrates the Exodus of the Jews

from Egypt. It was always my Zayde's seder, never my Bobbe's

(grandmother's). With solemn demeanor, my Zayde would recite the tale

of the Exodus in Hebrew, chanting in garbled sing-song from the Haggadah

, the ceremonial guide to the meal. Occasionally, he would pause in his litany

to silence the idle chatter of the women.

Zayde

Bobbe

Bobbe

My Zayde's Seder

My Zayde's Seder

I loved my Zayde's seder. I had a special role, seated at his right

hand, asking the Four Questions in a self-righteous soprano. If I stole the

hidden matzo, the afikomen, and returned it, I was rewarded

with the promise of a cap gun, a peashooter, or another instrument of destruction.

And, being a man, I could join my Zayde in hushing the women, for

whom at other times I showed deference and respect.

The

familiar and soothing chant in the background, cradled by a soft pillow

to demonstrate how the Lord had brought His people from slavery and oppression

to freedom and comfort, warmed by the sweet Manischewitz that even the youngest

child was permitted to drink, I leafed through the wine-stained pages of

the Haggadah, dwelling on the illustrations that appeared every few

pages. The ten plagues were not represented in as much gory detail as they

might have been, but they were a close second to The Crypt of Terror,

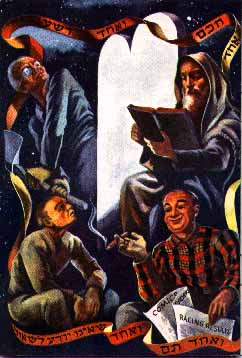

my favorite comic book.  The Four Sons were depicted in modern times; my favorite was the Simple

Son, a pot-bellied balding man, chomping on a cigar, reading the racing form.

Even he deserved to hear the tale of our people's deliverance.

The Four Sons were depicted in modern times; my favorite was the Simple

Son, a pot-bellied balding man, chomping on a cigar, reading the racing form.

Even he deserved to hear the tale of our people's deliverance.

The seder concluded with songs, the last of which was Had Gadya--"One Lone Kid." I learned later that the song was a parable describing the fate of the sequence of nations that had attempted in vain to destroy the Jewish people. But at the time, being only five, it was a pleasant children's game-song, rather like "I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly." It began:

And

then...and then...there he was.

How else should he look? A tall skeleton, shrouded in a dark brown frock,

whose loose pointed hood partially obscured the leering skull. In his hand,

a scythe. The grim reaper was poised above the bearded slaughterer, ready

to make his move.

How else should he look? A tall skeleton, shrouded in a dark brown frock,

whose loose pointed hood partially obscured the leering skull. In his hand,

a scythe. The grim reaper was poised above the bearded slaughterer, ready

to make his move.

When we would come to this point in the song, everyone would pound on the table, stamp feet, and sing the frightening name with feigned terror. The song and the seder concluded with a final verse, in which The Holy One Blessed Be He comes to slaughter the angel of death, but this seemed anticlimactic to me.

I met him again in the hospital. A friend who served as a physician on a Navajo reservation once told me that Indians are afraid to go to the hospital, regarding it as the house of death.

At age seven, I was one of the last to come down with polio, before the vaccine. I got off fairly easily, the major disability being a weak left foot. In an attempt to reroute tendons to strengthen my foot, my doctors admitted me to the hospital at the age of nine for surgery. A few days after the operation, my father visited me. As we sat chatting, he burst suddenly into tears .

"Bobbe Chaia

is dying, Michael," he sobbed. He had just come from visiting his mother

at a neighboring hospital. Although we visited Bobbe Chaia every

week at my Uncle Louie's house, where she lived with his family, I barely

knew her. She was the oldest woman I had ever seen,

who walked haltingly with a cane, but mostly sat, an exiled Czarina. I

would be led reluctantly to her to receive her blessing. She would draw

me to her prune-wrinkled Tartar face, murmuring blessings-"a gezunt in deine

bayne (a health in your bones)' and imprecations against the Devil-"Kayn

ein hora (no evil eye)." When she had finished with me, receiving no response

since I spoke on Yiddish, she would release me.

Now the malachamovess had left the pages of the Haggadah, and was coming for her. What was really scary about him, though, was what he could do to my father. I had never seen my father cry, and here he was, sitting at my bedside, sobbing like a child. My father...Dr. Ingall...who was supposed to be so big, and so strong,and the malachamovess could make him cry. Hoo ha! Two years later, I found out that he could even make my father howl.

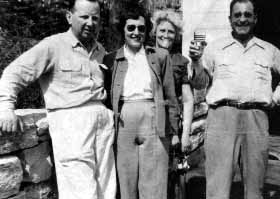

Each winter,

we would spend several days with our friends, the Kaplans,

at their home in rural New Hampshire. Winters were colder then, with much

more snow. Isolated in a town of twelve hundred, the Kaplans filled their

house with guests from the city. We filled all the beds and spare cots.

I slept on the living room sofa .

One Sunday

morning, I was awakened by the sound of my father, screaming in pain from

another room. There were no words, just howl after howl. From under the warmth

of my quilt, I tried to pretend it was a dream, His howls alternated with

moans. I thought that his boils had come back. A few months befoe, he had

come down with a case of severe boils on his buttocks. He had probably picked

up the infection in the hospital where he worked, and the germ was resistant

to the usual antibiotics. His boils had to heal by being lanced and drained,

Staring in fear and wonder from the doorway, I would watch his silent grimaces,

as my mother would lay moist gauze on the angry red craters covering his

buttocks. Now, heart pounding as I inched fearfully toward the sound of my

father's howls, I understood that when the Lord had visited the plague of

boils upon the Egyptians, he was not talking about a few zits. In the dining

room, my father stood screaming in pain, but there were no boils. My mother

explained that a telephone call had come from Boston, informing them of my  Uncle Louie

Uncle Louie

Uncle Louie's sudden death from a heart attack. The malachamovess

again. Hoo ha!