HUGH SAYS IT'S OK if I write this story and use his real name. Hugh comes to see me every week at the program I work at for former back ward patients of the state hospital. Hugh comes whether or not he has an appointment. At first, he didn't like me. I wasn't sure why. After three visits, he asked, "You probably don't remember me, do you, Dr. Ingall, but you came to my house in 1972 when you were at the Providence Mental Health Center, and you called the police, and you committed me to the IMH [state hospital] and I lived there for four years and I forgive you now Dr. Ingall because fear has no end in itself and we have to find shoes into the future. Do you know what REM says about it, Dr. Ingall? It says from the soul and five more times." I didn't remember the Hugh that stood before me, wild blonde-gray hair to his shoulders and full hermit's gray-blonde beard, all matted and in disarray. I did remember the visit and the house, and a threatening, wild, psychotic young man. [I myself was a wild young man at the time whom some took to be a bit psychotic.]

The other staff call him Hughie, even though I ask them to call him Hugh. Hughie is a little boy's name, and Hugh is forty-eight. But they are right. Hugh looks like a little boy. He smiles at you engagingly. He wears shorts with the waist pulled up to his chest, a T-shirt, and sneakers with dark socks. He walks with a loping shuffle...like a little boy. I have taught Hugh a few social amenities. He now shakes my hand with his right hand, rather than extending the left. But I could never teach him to tie his shoes. He simply couldn't do it. He'd walk around like a little boy with his shoes untied, and, like his mother, we would nag him to tie his shoes. So we bought him sneakers with Velcro straps. I wondered if it was a physical problem of dexterity, but he could play the piano. He seems fixed in time at eight years old.

When I first met him two years ago, he was

still a wild man, bursting from his apartment into the street, cursing

at

passers-by, screaming, menacing, threatening. Was it schizophrenia?

Was it too many bad trips? He had been on every

medication known to psychiatry over the last twenty years, and nothing

had really helped. So we put him on Clozaril, the

"miracle drug" for schizophrenics whom nothing could help. And a miracle

it was. Hugh stopped yelling, stopped cursing,

became more engaging and social. His speech slowed down from the endless

rapid-fire stream-of-consciousness that spewed

up through his throat into the world.

As Hugh the person emerged, he turned out to

be a musical genius. An idiot savant, if you wish, since a man with a

high school education who can sing Dvorak's Stabat Mater, the Jefferson

Airplane, and 3 Dog Night, and who also cannot

tie his own shoes might qualify for the title. We began to exchange

tapes and records. He lent me an ancient LP of Lotte Lenya

singing Kurt Weill songs that is to die for. I gave him fat Bulgarian

women singing chants through their noses. He gave me a

heavy metal album with a grotesque cover of a huge mouth casting forth

its fury into the world. Was it music? schizophrenia?

or was it the old Hugh?

From time to time, I would attack his residual

symptoms head on. I would ream him out for wearing dirty clothes to our

sessions. If I could smell him, I made him sorry for the rest of the

day. I gave him a bottle of Dr. Bronner's castile soap with

the bizarre messages in fine print on the label. "It's the soap of

schizophrenics and the schizophrenic of soaps," I told him.

He began to shower three times a week as ordered. He stopped smelling.

I snatched the mucus-encrusted wool stocking cap

from his head, threw it in the wastebasket, and gave him a new one.

I forbade him to wear it between May and November. He

let me trim his beard a bit at each visit until it became quite handsome,

and then one day, he shaved it off himself.

Today, at his long-standing invitation, I stop

by his apartment to see and play his keyboard. The program owns a handsome

Victorian mansion which has been converted into apartments, some single,

most for two. Hugh's roommate is also my patient,

a man of forty given to military camouflage, bullet vests, and posters

in his room of Nazis, with an occasional hand-lettered sign

reading, "FUCK".

Hugh invites me in, bowing and scraping in

apology. "I'm sorry it's so dirty here Dr. Ingall. Dave does the cleaning

mostly probably you're angry with me you must hate me." I can see that

Hugh has made a valiant attempt at straightening up

and picking up the room. But he points to every dustball as a monument

to his sins: "I'm sorry Dr. Ingall you must see that

dirt and say he's no good." Schizophrenia produces a two-and-a-half

pack a day habit. I knew that when I got home, my clothes

would reek of smoke.

Hugh's keyboard is the dream come true for

a young man of the 60's. A Fender Rhodes keyboard sitting atop a large

speaker

with a loud pedal. Hugh hasn't played the keyboard in 20 years, and

this was to be its legendary return. I play first. Hugh begins

to talk about John Raitt, so I play "If I Loved You," from Carousel.

Hugh begins to sing it. He has a mystic lovely high tremor

of a voice.

Unfortunately, in his haste and eagerness to

make his home presentable, Hugh has forgotten to clean the keys,which are

covered with the grit and grime of the 70's, 80's and 90's. But the

sound is true. It isn't exactly a piano, nor is it an organ.

It is the mother of all keyboards: a melange of harpsichord, celeste,

glockenspiel and piano. Hugh asks for something classical,

so I play a Beethoven Sonatina. It isn't Wanda Landowska, but it isn't

bad, either.

Then Hugh plays the Moonlight Sonata. By ear.

He has the harmonies and the fingering down pat. It is magical. He is a

little boy, and an idiot savant, and a man growing old and wise and

a schizophrenic and a fried brain and a patient and a

colleague and a friend.

Hugh thanks me for coming. I thank him for

playing again. My bike has a flat, and he helps me fix it by smoking and

encouraging me with his chatter. "You probably didn't like the Moonlight

Sonata Dr. Ingall you're probably mad at me that

I made you come over and hear it and now you have a flat and you'll

never get home and you'll send me back to the IMH

and I don't blame you."

On Sunday morning, Hugh's

roommates didn't hear his familiar cigarette cough for hours, and when

they went up,

they found him on the floor in the bathroom.

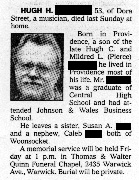

It was probably a heart attack. His sister said he always spoke of how

lovely

Swan Point Cemetery was, where his parents were

buried, but Medicaid only pays $1800 for a funeral, and the maintenance

fees at Swan Point are so high. So, they had

him cremated and scattered his ashes on his parents graves at Swan Point.

There

was a memorial service. I brought the Mozart

Requiem to play, as it was the piece he was going to sing with me at the

Providence Singers Summer Sing two days later.

The last time I saw him, I told him he would have to shower if he wanted

to

stand next to people and sing. When he came to

my last Singers concert two weeks ago, we drove him home, bought him the

usual large coffee and a chocolate donut, and

he threw his red stocking cap in the trash in return. Guess he won’t need

it next

winter. His sister told me that when Hugh got

a standing ovation when he sang "You'll Never Walk Alone" at his high school

graduation. He never did walk alone.